Corporate tax is down, says OECD report | OECD

According to a leading think tank, eight of the world’s major industrialized countries either cut their corporate tax rates last year or announced plans to do so.

In the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development’s annual report on tax changes around the world, released on Thursday, the think tank said Japan, Spain, Israel, Norway and Estonia had all lowered their corporate income tax rates in 2015. announced by Italy, France and the United Kingdom, while Japan planned further reductions.

The OECD said the 2015 downward trend accelerated as governments around the world emerged from the aftermath of the 2008 banking crisis and began to use their fiscal policies more aggressively to chase GDP growth.

In particular, countries competed to offer foreign multinationals the most attractive tax rate in order to attract investment. “With respect to corporate tax, rate cuts had generally slowed after the crisis but appear to be picking up,” the report said. “The trend seems to be gaining new momentum.”

The OECD’s findings may make for uncomfortable reading for many politicians who have recently claimed to be leading the battle to make big global corporations pay more taxes. A series of revelations about ultra-low tax bills among several of the world’s biggest companies – including Apple, Vodafone, Starbucks and Google – have sparked widespread public anger. The OECD suggested that corporate tax cuts were partially offset by increases in other taxes such as VAT, fuel and car taxes.

Many tax justice and inequality campaigners have pointed out that this trend hits poorer people the hardest. The Tax Justice Network notes that it “redistributes wealth upwards.”

“Governments fill the gaps [from corporation tax cuts] by levying higher taxes on other, less affluent segments of society, or cutting back on essential public services, tax ‘competition’ increases inequality and deprivation,” the Tax Justice Network said.

OECD experts said lowering corporate tax rates could indeed boost GDP, but was also likely to put pressure on other countries to follow suit and reduce the tax rate. tax they levy on corporate profits. Critics of tax competition have called it a “race to the bottom”.

The OECD said the average tax rate on corporate profits fell from 32% in 2000 to 26% in 2008. The rate of decline then slowed – the average reaching 25% last year – but now seems accelerate again, said the OECD. .

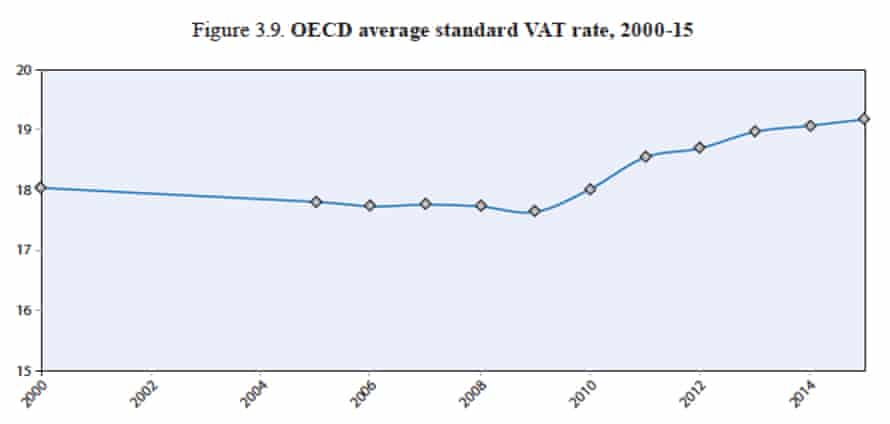

Meanwhile, the average VAT rate – a tax that hits the poor the hardest – fell from 17.6% in 2008 to a record high of 19.2% at the start of 2015.

The UK was not among the OECD countries to cut corporate tax rates last year, but then-Chancellor George Osborne announced the rate would drop steadily to 17% by 2020. It was 28% when Osborne took office in 2010. He has repeatedly boasted of giving the UK the most competitive corporate tax rate of any G20 country .

Speaking at a press conference on Thursday, OECD tax experts insisted world leaders were increasingly aware of concerns that aggressive tax competition was leading to greater income inequality and riches.

“In the past, tax policy has focused largely on revenue collection… [GDP] growth,” said David Bradbury, head of tax policy and statistics at the think tank.

“People have often left the issue of income inequality – redistribution – to other policy levers, especially public spending. But tax policy also has a critical role to play in addressing these important inequality issues.

Earlier this month, leaders attending the G20 summit in Hangzhou called on the OECD and the International Monetary Fund to explore ways to use tax reforms to better support GDP growth while reducing inequality. income and wealth.

As progressive personal and corporate income tax rates are falling in many countries, OECD experts said governments have other options to explore. These include wealth taxes and measures to remove tax breaks on mortgage outlays and pension contributions – incentives that largely benefit the wealthiest people.

More broadly, the OECD said industrialized countries wishing to raise tax revenue could do much more to tax property and carbon-intensive fuels such as coal. “The potential to generate revenue efficiently through property taxes, particularly through recurrent taxes on residential property, is not fully realized,” the report concludes, although it found that the most high were in the UK.

Meanwhile, OECD figures showed countries were failing to align taxes that impact the environment with international ambitions to transition to a low-carbon economy. In particular, road transport has been heavily taxed while other sectors account for 85% of CO2 emissions.

“The potential for harnessing the power of taxes as instruments of environmental policy is significant,” the report says, noting that there are currently “unusually low taxes on some of the most environmentally damaging fuels, including the coal”.

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/irishtimes/6D3PQFR4HASJYP5NYJXVM66GAM.jpg)